HRD Deep Dive: How has COVID reshaped the gig economy?

- 6 Min Read

A true phenomenon of the modern working world, the gig economy is a vast and fast-growing sub-section of the global workforce. However, COVID-19 has served to rupture this to its core, and may well prove to change the complexion of it entirely. To simplify this complex situation, we’ve composed a run-down of what’s happened so far, and what may be still to come.

- Author: Sam Alberti

- Date published: Aug 4, 2020

- Categories

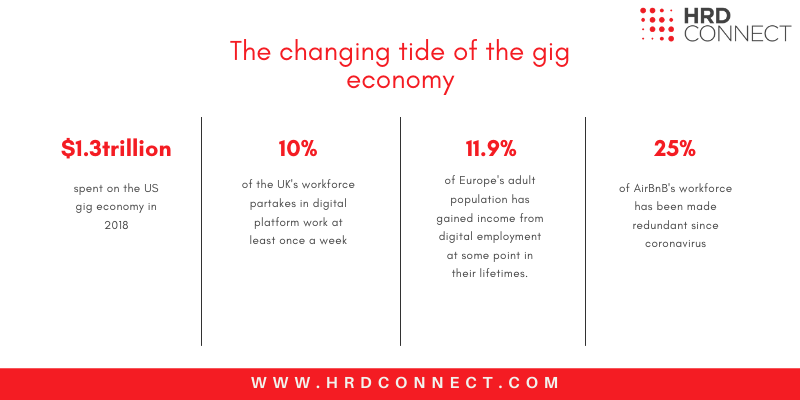

Research shows that an estimated 53 million people took part in ‘gig’ work in the US in 2018. In monetary terms, that equates to roughly $1.3trillion spent on the gig economy. Globally, the number rises to $4.5trillion, and from a certain perspective, this paints a rather alarming picture of the future of work.

For context, these figures are not stagnating. In the UK alone, the number has doubled in recent years; now at over five million. What’s more, 10% workers in the UK now partake in digital platform work at least once a week, and nearly 2/3 of this number are aged 16-34. That’s 1/10 people bereft of the support, protection, representation and financial stability of permanent employment. So, surely this is as bad as it gets?

Enter COVID-19: the most damaging health crisis we’ve seen for a century. With the demand for many services plummeting and organizations having to cut costs wherever possible, contractors and gig workers have perhaps been some of the hardest hit by the global pandemic. This has served to further expose the gig economy’s precarious and fickle nature.

However, there could be a silver lining. There is a feeling emerging that the current crisis could spark legislative changes that would offer a greater degree of protection and security to gig workers through the pandemic and beyond.

Given the complexity and fast-changing nature of the situation, we took the time to summarize and interpret the issue.

What damage has been done?

The rapid growth of the gig economy can be largely attributed to the meteoric rise of website or app-based employment; Uber, Deliveroo, Handy and Upwork all stand out as key players. In fact, studies have estimated that nearly 12% of Europe’s adult population has gained income from digital employment at some point in their lifetimes.

However, this in itself is the very reason why gig workers have taken such a hit during the pandemic; the services offered by such platforms have plummeted in demand.

For instance, with the travel industry naturally faltering, online rental marketplace AirBnB was forced to make an emergency update to its extenuating circumstances policy, allowing guests to cancel bookings for trips starting before 31 May, with a full refund and no penalty fee issued. By extension, this meant a loss of income for many of the platform’s 700,000 hosts.

Food delivery platform Deliveroo took similarly drastic measures in response to the pandemic, announcing in April that it was laying off roughly 15% of its workforce. With something of a pattern emerging, several more digital employment organizations proceeded to follow suit, with Uber (14%), Lyft (17%) and AirBnB (25%) all unveiling significant workforce cuts.

Though mere snapshots of the situation, these figures are strongly indicative of a seismic landscape change within the gig economy. Not only do these workers rely on a steady demand for the services they are providing, but crucially, such services can generally only be offered if there is a safe environment in which to do so.

Unfortunately, the majority of gig work comes with a significant health risk during COVID, and therefore, the complexion of this industry has been almost entirely reshaped.

Could this damage spell lasting change for the gig economy?

In spite of the difficulty many are facing, there is a growing feeling that COVID-19 has shed some light on vulnerable groups in society, and may spell some significant change for the gig economy.

At the lower level, many examples of such change have already been put into action, with organizations recognizing the added strain on gig workers, and implementing new measures to address this.

For instance, following on from the earlier amendment of its cancellation policy, AirBnB publicly released financial relief guidance for all hosts, compiling a list of resources being offered by local and national governments.

Uber made a similar gesture shortly after, unveiling its new ‘Work Hub’: a central, digital location for drivers to view a selection of temporary work opportunities as a way to recoup earnings lost during the pandemic.

“The most important thing we can do right now is support drivers,” said Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi in an official blog posted by the company to announce the launch.

“They’re doing essential work to keep our communities moving as we fight this virus, but with fewer trips happening they need more ways to earn.”

It is clear then, that there is scope for organizations to take tangible, effective measures in order to provide some respite to workers hit hardest by the pandemic. Not only will this remedy the current situation for many, but it will perhaps help to set a precedent for gig workers receiving more traditional rights, representation and protection in their roles.

On a higher level, however, many feel that the increased attention on the gig economy could set the stage for legislative action to be taken. The consensus is that policymakers are the key stakeholder group who are yet to seriously intervene in this space; something that could be on the horizon following 2020’s events, and could officially award greater rights to gig workers.

In fact, many would argue that in the UK, the ball is already rolling. In response to the crisis, the government motioned that the introduction of IR35 (legislation compelling contractors to pay broadly the same tax and National Insurance contributions as employees) would be delayed.

Similarly, in March earlier this year, French authorities ruled that its Uber drivers would officially be granted employee status. It is thought that this ruling could have a knock-on effect on other gig economy employers in France.

Though small steps, such legislative action is unprecedented when it comes to the gig economy and its workforce. Consequently, there is now a glimmer of hope that the effects of COVID-19 could provoke a major shift in organizational and governmental attitudes when it comes to contractors, freelancers and platform workers.

What does this mean for leaders?

As freelance, contract and platform workers adjust to the changing gig economy, so too must employers and HR leaders.

One scenario, for instance, would see organizations employing the services of gig workers at a much greater rate. Research conducted by Aon even claims that more than 1/4 of European HRDs believe that their workforces will be comprised of 51-75% gig workers in five years’ time.

In turn, regulations protecting gig workers are likely to strengthen, and naturally, this is bound to cast a more intense light on HR practices when it comes to the bureaucratic treatment of these practitioners.

What’s more, Aon’s report goes on to point out that 67% of gig workers would feel more positive towards the organisation if benefits were in place. At present, just 31% are offered benefits.

This ties in with another troubling element of the modern gig economy; the demand for special skill is thought to outweigh the available supply. As a result, smaller organizations will encounter difficulty if they are not able to offer top salaries.

With this in mind, the incentive to offer protection and benefits should be even greater for HR and business leaders in 2020.