-

Provided by

- Date published: Feb 22, 2022

- Categories

It’s long been known that the media industry struggles in its battle to diversify. Studies suggest that the likes of the Washington Post, Vox Media and The New York Times all still operate with over half of its staff identifying as white, with a large portion of those in senior leadership positions.

The Financial Times is working hard to change those statistics, with an impressive DE&I agenda that goes beyond words on a page.

We speak to Kirsty Devine, global HR leader at The Financial Times on the work they’ve been doing in the DE&I and early career talent space to build a more diverse workforce behind the publication, as well as lead the way for the wider media industry.

Battling brand perception

“The Financial Times has been operating for more than 134 years so there is sometimes a misconception that our rich heritage equates to us being overly traditional or archaic,” begins Kirsty.

“That couldn’t be further from the truth. Our business model has evolved at pace in the last 15-20 years and our innovations have led industry wide changes.”

The Financial Times is certainly one to pave the way for others. Historically, it’s been one of the first publishers to establish a paywall and diversify their portfolio. Nowadays it’s no different. The FT has just recently published their ethnicity and gender pay gaps in the UK and the US (the latter is not required by law), all aimed at being as transparent as possible about the organisation and their commitment to change and diversify.

“We’ve had to diversify ourselves, and it’s meant that to establish that, internally we also need to have diverse voices, diverse perspectives, diverse representation,” says Kirsty.

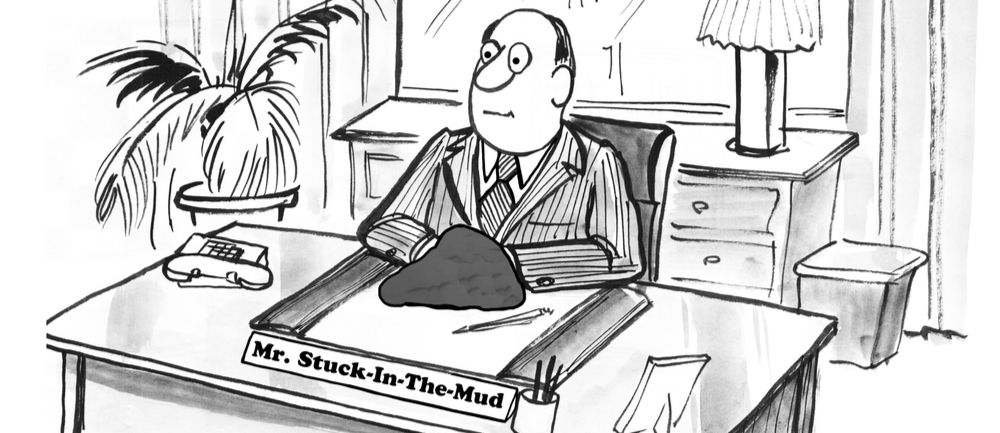

But the build-up of diverse voices at the FT hasn’t always been an easy path to follow. Like many larger and older organisations, there can be a case of being stuck in the mud as they try to innovate.

For Kirsty, recruitment was a particularly sticky issue to overcome.

“I remember when I started at the FT and we’d be trying to hire technologists, we’d be like ‘where do we find them and how do we tell them there is a great career they could have at the FT,’” says Kirsty.

“But people didn’t associate a cool technology career with the FT.”

This is beginning to change though. With the work The Financial Times is doing, they are slowly starting to shift the needle on what people associate with the brand and more broadly, the media industry.

Well known for its lack of diversity, the media industry has a long history of small openings for people to enter and grow – much less so people from diverse backgrounds. And as much as it has improved over time, there is still a long way to go.

Kirsty knows that the Financial Times hasn’t been innocent in the past. She explains that, due to the organisation’s huge success and legacy, the Financial Times has never been a place for workers to pass through. Quite often, journalists come to the business at the pinnacle of their career and, as a result, stay a long time. While that has its benefits, it means upward movement within the organisation can be few and far between.

“So we’ve had to look at all those structural things to ensure people have opportunity at the FT” says Kirsty.

Striking the right balance can be tricky business, which is why the FT is focusing on early career talent as a way of overcoming this issue. The earlier an employee can jump aboard, the longer their trajectory upwards will be.

Threading diversity as a constant through talent decisions is a must, and must be supported by everyone in the business, from senior leadership to the wider employee group.

“It needed to change… we wanted to diversify our people and we also needed our content to be reflective of our diverse societies,’” says Kirsty.

To keep the business on track, Kirsty shared some of the targets and progress. As well as keeping everything published on their website, the FT also has internal goals to reach.

-

- By 2024, the FT aims to have 25% of their UK workforce identify as an ethnic minority (currently 21.8%) and 40% in the US (currently 33.7%).

- They also aim to have 10% of the workforce consider themselves to have a disability (currently it’s 3.7%) and another 10% who identify of LGBTQ+ (currently 4.9%).

- Senior management at the FT has a goal to have 20% of its people identify as an ethnic minority (currently 13.6%).

Alongside these goals, the Financial Times also published its gender and ethnicity pay gaps last year and have made all the information from previous years readily available too.

Building bridges with the FT News School

Financial Times’ early career focus is geared towards opening the door for younger talent to peak behind the curtain of the industry. The reason for this is two-fold: to educate younger and prospective employees, and to offer the opportunity to grow their network in what is otherwise a difficult industry to crack.

“Many people don’t know anybody in the media industry,” says Kirsty. “So it’s about opening those doors and giving that insight to communicate that the industry is accessible.”

The way the Financial Times is approaching this is through the initiative called “FT News Schools.”

Started in the UK in 2020, The Financial Times partnered with organisations like The Prince’s Trust and the Emma Bowen Foundation to launch a programme designed to educate and offer opportunities to younger talent (aged between 18-21) who would otherwise struggle to get close to the industry.

“Students could apply for a slot at the FT News School, and they came along and did a two-week programme,” explains Kirsty.

“The sessions were an hour and a half each week on a different topic.”

“They [the students] would dial in and hear from two speakers and then they’d have the opportunity to ask questions afterwards.”

“It was so successful in the UK in terms of engagement that we had with the students… we’ve now expanded this to the US as well.”

But what has been an interesting development since the programme’s launch is its organic evolution from an industry showcasing tool into an effective recruiting tool for the publisher.

“When we brought it to the US, we were only going to offer 20 spaces on the programme, but we had 30 fantastic applications so we accepted everybody,” says Kirsty.

After the programme finished, each student attended a graduation ceremony and had their name published in The Financial Times the following day.

“It felt like [the programme] had an impact on the students and they were now considering their options,” says Kirsty.

On top of that, each student is offered an opportunity to be mentored by someone at the FT or one of our partner organisations for six months. This is geared towards keeping those connections alive with people in the industry, and really helping younger talent build an effective network of experts in their field of interest.

And the plan is working. The FT has since hired 5 students from the programme as well as making a recent job offer to one of the students as a reporter, with many more sure to follow.

Kirsty believes that The Financial Times’ progress in the space will benefit other publishers to achieve more with their D&I agenda as well.

“We’d love for other companies to think about doing this as well, and we can provide the blueprint for them to do that,” says Kirsty.

“This isn’t an FT thing, this is a media thing. If we can help you to launch your own News Schools, then we’re happy to provide the guidance, tools and insights on how we did it.”

The Financial Times will be running the FT News Schools again in the UK and the US this year, and plans to keep doing so due to the huge success. Alongside these, the organisation will continue to keep running their regular internship programmes, too.

When talking about the internship programmes, Kirsty mentions the specific approach the FT takes to diversify their incoming students.

“We’ll typically try to hire students from non-journalist colleges… We tend not to go to Columbia, Harvard or Yale, we’ll go to the lesser known J-schools and hire from there,” says Kirsty.

Breaking barriers for the future

For diversity and inclusion to be truly successful, one of the biggest factors to be in play is accountability.

“I don’t think we would have gotten anywhere near as far in our D&I journey without accountability,” says Kirsty.

“It’s not just a HR thing, or a CEO thing – it’s an everybody thing.”

As part of this, Kirsty also praises the support and impact of employee resource groups at the FT. These people are the internal drivers of the D&I discussion.

“They are just fantastic in creating that ground swell and that movement to want to change, and to also spark that in other people,” says Kirsty.

“To have these groups of people pulling together has had a great impact on our diversity agenda.”

This way of working, communicating and driving change is also reflective of working together as one organisation, including everyone – which is the ultimate goal of diversity and inclusion.

Following the appointment of the Financial Times’ first Head of D&I in 2020, the team has now grown into four people dedicated to driving the agenda.

“Our Head of D&I at the beginning of this year has refreshed our D&I strategy. There’s a number of things in partnership with the business and the board that he has developed that are going to be important between now and 2025,” says Kirsty.

These include the following:

- Advancing our Inclusive Culture work to ensure all employees have a voice and are able to be at their best

- Extending our focus on diverse talent in the media industry and breaking down the barriers to progression for under represented talent

- Communicating our D&I work internally and externally by better promoting our industry leading content to diverse audiences and transparently reporting on our progress

The FT appears ready for the challenge that the war for talent will bring. It has already proven itself as a creative thinker in the space, and is exploring ways of bringing people on board that not many others are doing.

“I think we’ve got a good foundation and we offer a lot for people when they get here… but I think we’ve got more work to do around other demographics,” explains Kirsty.

This includes other pillars of diversity such as disability. For this, Kirsty says the FT has some improvements to make.

But overall, progress looks good.

For a publisher so committed to change, it’s refreshing to see the power people can have in an environment willing to listen. Combined with technology that can help detect problems, it is an exciting time for the business.

The Financial Times is, quite frankly, down with the times.